Hi everyone,

Today, we're tackling a big topic: a comprehensive overview of the global economy.

I'm sure you've all seen the headlines: the US hitting its debt ceiling again, the Japanese stock market hitting new highs, companies moving their factories to India, and so on. You might have heard these things but haven't really thought about what they mean for the current state of these economies.

In this article, we'll analyze the global economy from a professional perspective, focusing on macroeconomic trends. We'll start with a broad overview to give you a general understanding. Then, we'll dive deep into some major economies, exploring their strengths, weaknesses, and potential risks.

I'm not an economist, and I won't be making any wild claims. I've simply absorbed a lot of professional research reports and insights from industry insiders. I'll share what I found most reasonable and organize it in a way that makes sense. Of course, these are just my opinions.

I believe that looking at data and the current situation is only one aspect. It's equally important to understand how professionals analyze a country's macroeconomy – their perspectives and thought processes. I believe this will be particularly helpful for you.

Finally, I'll briefly summarize my own approach to understanding a country's economy, including potential pitfalls. Consider this a sneak peek into my little knowledge tree.

So, how about it? Plenty of valuable insights, right? Feel free to bookmark this article if you find it interesting.

The Global Economy: A Snapshot

We know that the global economic theme in 2022 was crisis: inflation, interest rate hikes, energy crisis, etc. The theme for 2023, I would say, is recovery. Inflation and the energy crisis are generally under control, and interest rate hikes are mostly over. While every country has its own economic challenges, the overall situation is better than expected, especially for the US and India, whose economies have been surprisingly strong.

Think of it this way: in 2022, the global economy was hit with a serious illness. It was weak and fighting the disease, causing a fever – in this case, inflation. Countries raised interest rates, a measure that hurt themselves as much as it hurt the disease. But regardless, the priority was to control inflation.

Now, in 2023, the recovery seems better than anticipated. The headache is gone, appetite is back, and the economy can even walk a little. The theme for 2024 is normalization, a return to a normal state without lasting damage. This means restoring consumption and investment, controlling inflation, and gradually cutting interest rates – essentially what many countries call a "soft landing," avoiding a recession.

I've compiled a list of major economies and their expected 2023 growth rates. Some quarterly data isn't available yet, so I've used forecasts, which should be fairly accurate. This list includes economies with GDPs exceeding \$1 trillion.

India takes the lead with the fastest growth at 7.3%, followed by China at 5.2%. Saudi Arabia and Germany are at the bottom. Saudi Arabia's position is understandable due to its reliance on oil, and frankly, they already won big in 2022. Germany's struggles in 2023 might come as a surprise.

Interestingly, recent news reports that Japan's 2023 quarterly economic data fell short of expectations, allowing Germany to overtake them as the world's third-largest economy.

Wait, didn't we just say Germany was second to last, right above Saudi Arabia? How did they surpass Japan?

The news itself is accurate, but the methodology differs. Growth rates are usually calculated using a country's own currency, adjusted for inflation. The GDP figure used to declare Germany larger than Japan is nominal GDP, which is converted to US dollars based on the current exchange rate.

So, why did Germany overtake Japan as the third-largest economy? The answer lies in exchange rates. Japan's real GDP has been growing in recent years, but the yen has depreciated significantly. This depreciation caused its nominal GDP, when converted to US dollars, to plummet, allowing Germany to surpass it.

Imagine if Japan used its foreign exchange reserves to buy up the yen – wouldn't that maintain their ranking?

This example highlights how headlines can be misleading. Hearing that Germany is poised to overtake Japan as the third-largest economy might lead you to believe that Germany is strong and Japan is weak. In reality, Japan isn't doing as poorly as suggested, and Germany isn't as strong. Neither is likely to hold the third-place position for long.

That was just an appetizer. Now you're probably curious about why Germany is struggling, how the US and India are thriving, and what's going on in Japan. Don't worry, we'll get there.

Japan's Economic Puzzle

Let's start with Japan. In 2023, Japan's GDP grew by 1.9%. For an economy stuck in a long-term slump, this isn't bad. However, two consecutive quarters of negative growth have technically put it in a recession. Inflation, a battle Japan fought for three decades, has finally emerged from deflation and hovers around 3%. Unemployment remains characteristically low, with near-full employment. Meanwhile, the stock market is exceptionally strong, the yen is incredibly weak, and the central bank is considering abandoning a decade-long unconventional monetary policy.

If I had to describe Japan's economy in recent years with one word, it would be "twisted."

They yearned for inflation, and now that it's here, they're not happy – twisted. The central bank is stuck between a rock and a hard place regarding interest rates – twisted. The weak yen hurts but helps exports – twisted. Food prices are soaring, but wages remain stagnant – twisted. The real economy is mediocre, but the stock market is booming – twisted.

Headache-inducing, right?

Japan's situation is arguably the most complex and perplexing among major economies. Let's unravel this knot, starting with inflation.

For the past three decades, Japan's inflation rate has hovered around zero, a constant struggle against deflation. Their inflation target has been 2%, a seemingly impossible goal. This makes the Bank of Japan arguably the most desperate central bank in the world. They've exhausted all conventional easing policies.

If there were an award for central bank innovation over the past two decades, the Bank of Japan would undoubtedly win it. Note that this is sarcasm, not praise.

They pioneered quantitative easing in the early 2000s, a radical monetary policy at the time that's now considered standard. But that wasn't enough. The Bank of Japan then introduced two unconventional measures: negative interest rates and yield curve control.

These might sound complex, and the actual implementation certainly is, but the underlying logic is simple. Negative interest rates lower short-term rates, aiming to make borrowing practically free for banks and financial institutions. Yield curve control essentially suppresses long-term rates, affecting things like mortgages and corporate financing. The goal is to reduce borrowing costs for almost everyone in the economy, encouraging money circulation and stimulating growth.

Comparing interest rate curves from different countries reveals a comical contrast. While the US Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank have rollercoaster-like curves, Japan's remains flat, with long-term rates also suppressed. Some jokingly remark that even Japan's yield curve is lying flat.

So, what happened recently? The US raised interest rates, causing the dollar to strengthen against the yen. Then came 2022 with global inflation and an energy crisis, further inflating the price of dollar-denominated goods. The depreciating yen meant that imports became even more expensive for Japan, especially energy and oil. This perfect storm finally brought inflation to Japan, a country known for its stable prices.

Some joke that Putin single-handedly achieved what Japan had been striving for over three decades: inflation. But is it truly a good thing for Japan? Not necessarily.

Japan's inflation is primarily imported. Prices aren't rising due to increased demand, but because imported goods are more expensive, forcing domestic prices to follow suit. This isn't ideal. The most significant price increases have been in food and commodities. Food inflation has surpassed 8%, while wage growth remains limited. In terms of purchasing power, real wages may have actually declined.

More expensive goods coupled with stagnant wages lead to decreased spending and declining consumption. This is why Japan's consumption hasn't returned to pre-pandemic levels, a stark contrast to the US, which we'll discuss later.

Consumption is the engine of a nation's economy. If consumption thrives, minor hiccups in other areas can be managed. However, if consumption falters, trouble looms. A fundamental problem facing most countries, except perhaps the US, is the inability to revive consumption.

While imported inflation seems detrimental, it's not entirely bad news for Japan. Although it suppresses consumption and the economy, it has achieved one crucial thing: raising awareness of inflation among the Japanese people. This was a significant challenge over the past three decades.

For so long, prices remained relatively constant, as did wages. Money held the same value whether it was in the bank or under the mattress, with interest rates near zero. However, recent years have gradually shifted this mindset.

People are realizing that prices do, in fact, increase. They understand that delaying purchases might mean paying a higher price later. This realization encourages them to spend when needed, boosting demand slightly.

In essence, while imported inflation has drawbacks for Japan, it has forced the population to acknowledge and adapt to inflation, accelerating the velocity of money and slightly boosting demand.

Now, let's address the elephant in the room: the Bank of Japan's dilemma. They face a difficult choice. Not raising interest rates widens the gap with the euro and US dollar, further weakening the yen. The past two years have already witnessed significant capital flight from Japan's private sector to overseas markets. Continuing on this path could severely impact the economy. Moreover, if inflation spirals out of control, the central bank would be forced into a reactive position, potentially derailing the nascent economic recovery.

On the other hand, raising interest rates would directly suppress the already struggling economy, further burdening domestic demand. Additionally, Japan faces a moral hazard. With the world's highest debt-to-GDP ratio, even a slight interest rate hike would significantly increase the government's interest payments. This creates an incentive for the Japanese government to discourage the central bank from raising rates.

The crux of the matter is that raising interest rates now would mean abandoning the long-standing unconventional monetary stimulus policies. This creates significant uncertainty for Japan's economy. Exiting an environment of near-zero borrowing costs, stable prices, and central bank support is a gamble.

Ironically, Japan has been implementing these so-called "special policies" for so long that they feel normal. Now, their talk of "policy normalization" feels somewhat abnormal. Imagine an animal accustomed to living in a zoo. Its survival upon returning to the wild is uncertain.

So, what is the Bank of Japan doing? They're treading carefully, taking one step at a time, preferring words over actions. They test market reactions before making any moves.

For example, in 2022, the Bank of Japan began gradually widening the yield cap on 10-year government bonds. They slowly increased it from 0.25% to 0.5%, carefully observing market reactions. This move triggered a wave of short-selling attacks on the yen and Japanese bonds, forcing the central bank to intervene by buying bonds and yen to counter these speculators.

After the market stabilized, the Bank of Japan, cautiously optimistic, raised the yield cap further to 1%. Despite some initial volatility, the market seems to have accepted this move. Now, they're hinting at further flexibility with the 1% cap, emphasizing a data-dependent approach. Their cautiousness resembles Tom Cruise navigating a complex mission in "Mission: Impossible," fearing that any misstep might trigger a market backlash.

2024 will be a crucial year for Japan. Major investment banks like JPMorgan and Goldman Sachs predict that the Bank of Japan will exit its negative interest rate policy and yield curve control in 2024.

The key question is whether they'll pull the trigger on interest rate hikes. What factors will determine their decision?

Currently, the Bank of Japan is focused on two key indicators: consumption and, perhaps more critically, wages. They've explicitly stated that their decision to abandon unconventional monetary policies hinges on whether wage growth can outpace inflation.

Why is wage growth so crucial? Because price increases occur at different paces and affect different sectors. In Japan's case, energy prices rose first, followed by food and industrial goods, and now, service prices are starting to rise.

Typically, wage increases are the last to materialize and are crucial for completing the economic cycle. Employers, understandably, are hesitant to raise wages unless absolutely necessary. This isn't to demonize employers or capitalism; it's simply a reflection of the slow pace at which labor, especially skilled labor, moves within an economy. This is particularly true in Japan, where job-hopping is uncommon.

Consequently, there's a significant lag in wage adjustments. While wages in Japan have started to rise, the pace is nowhere near the rate of inflation. In terms of purchasing power, real wages have been declining since 2022.

The Japanese government is actively encouraging wage growth. They've raised the minimum wage and implemented tax incentives for companies that increase salaries. The message is clear: wage growth is the current focal point.

Interestingly, Japan has a unique annual event called "Shunto," or "spring offensive," where labor unions negotiate with employers to determine wage increases for the year. These negotiations, typically lasting from January to March, set the tone for wage adjustments across various industries and company sizes.

While not a uniform figure, Shunto outcomes provide a benchmark. In 2023, the average negotiated wage increase was 3.6%, the highest in nearly three decades. This year, the target is reportedly 5%. The actual outcome remains to be seen, but it holds significant weight.

Currently, many of Japan's fiscal and monetary policies are essentially on hold, awaiting the outcome of Shunto. It's like a game of chicken between the government, the central bank, and the labor market.

While the real economy grapples with uncertainty, the stock market tells a different story. It's been on a tear, rising nearly 50% from early 2023 to February 2024, reaching its highest point in three decades. What's driving this surge?

There are three primary factors at play.

Firstly, the weak yen makes Japanese stocks attractive to foreign investors, particularly from the US. The market consensus seems to be that the yen has bottomed out at around 150 to the dollar. Further depreciation is likely to trigger intervention from the central bank. Buying Japanese stocks now is seen as a bet on both a rebounding yen and a continued stock market rally, a potentially lucrative double whammy. This has been a key driver of the recent surge in Japanese stocks.

Secondly, geopolitical factors have prompted global supply chain restructuring following the pandemic. As a major exporter, Japan stands to benefit significantly. Many high-value-added supply chains have shifted to Japan, particularly in the semiconductor sector, which has doubled in value over the past year. The weak yen further stimulates exports, benefiting industries like automobile manufacturing, which have seen their stock prices surge.

However, the consensus is that neither the weak yen nor supply chain restructuring is the primary driver of Japan's stock market rally. The most significant factor is corporate reform in Japan.

Now, "reform" might sound like a vague and drawn-out process. However, in Japan's case, it's quite specific and has had a tangible impact.

Japanese companies have historically prioritized stability. They didn't overextend during boom times and refrained from layoffs or prioritizing shareholder interests during economic downturns. Years of loose monetary policy had spoiled them. With ample cash reserves and little pressure to perform, many Japanese companies became "zombie companies," or at least had zombie departments and processes. This led to low stock valuations, with many companies trading below their book value (a measure of a company's net asset value).

A price-to-book ratio below 1 suggests that a company's stock price is lower than the value of its assets if it were to be liquidated. It's akin to saying that a company's assets are worth more than its market capitalization, making it an unattractive investment.

Many investors viewed the Japanese stock market as a value trap. With over half of listed companies trading below their book value, the government finally decided to act. After over a decade of discussions, they implemented a reform plan in 2022.

The core of this plan is to push companies with a price-to-book ratio below 1 to shape up or ship out. They need to increase profitability, return value to shareholders through dividends or buybacks, and demonstrate their worth to investors. Failure to do so could result in being delisted from the stock exchange by 2026.

This has spurred many Japanese companies to increase share buybacks and dividends since 2022, despite the challenges posed by the pandemic. This trend is expected to continue in the foreseeable future.

As Japanese companies start performing and distributing profits, investor confidence has returned, fueling the stock market rally.

But there's another crucial figure behind Japan's stock market surge: Warren Buffett.

Whenever I hear about undervalued and cheap markets, Warren Buffett comes to mind. He recognized the opportunity in Japan three years ago, investing approximately \$6 billion in Japanese financial companies. Last year, the 93-year-old personally flew to Japan to urge companies to prioritize shareholder returns through dividends, further solidifying his stance.

While Buffett, despite his reputation as the "Oracle of Omaha," cannot predict the future, his investment decisions carry weight. If Buffett buys, it signals a potentially undervalued asset. This has attracted many investors to follow suit, further fueling the rally.

While quantifying Buffett's exact impact is difficult, the Japanese stock market has surged by almost 40% since his visit. It seems like Warren Buffett has won, yet again.

To summarize, Japan's economic situation is complex and multifaceted.

Their long-awaited inflation has arrived, but it's not the type they hoped for – twisted. The central bank is in a bind over interest rates – twisted. The weak yen hurts but also helps – twisted. Food prices are rising while wages stagnate – twisted. The real economy is sluggish, but the stock market is booming – twisted.

The World Bank projects Japan's GDP to grow by 0.9% in 2024. However, the focus isn't solely on the growth figure. 2024 will be a pivotal year for Japan, determining whether they can escape deflation and transition smoothly towards a more conventional monetary policy.

The key challenges lie in shedding their dependence on unconventional measures and fostering a sustainable economic environment without triggering major shocks. This involves reducing reliance on central bank asset purchases and government borrowing.

Interestingly, several major Japanese banks recently raised their 10-year deposit rates from 0.002% to 0.2%, a hundredfold increase. This could be a sign of changing times. Japanese citizens might finally see a reason to keep their money in the bank, potentially influencing the future economic landscape. Only time will tell what unfolds.

India's Economic Surge

Now, let's shift our focus to China. According to official data from the National Bureau of Statistics of China, China's GDP grew by 5.2% in 2023. CPI inflation rose by 0.2% year-on-year, and the national urban surveyed unemployment rate averaged 5.2%. The central bank is currently in a cautious interest rate cutting cycle.

I believe it's important to provide you with this basic data. I'll be skipping over a detailed analysis of China's economy, as there are already many excellent professional reports available.

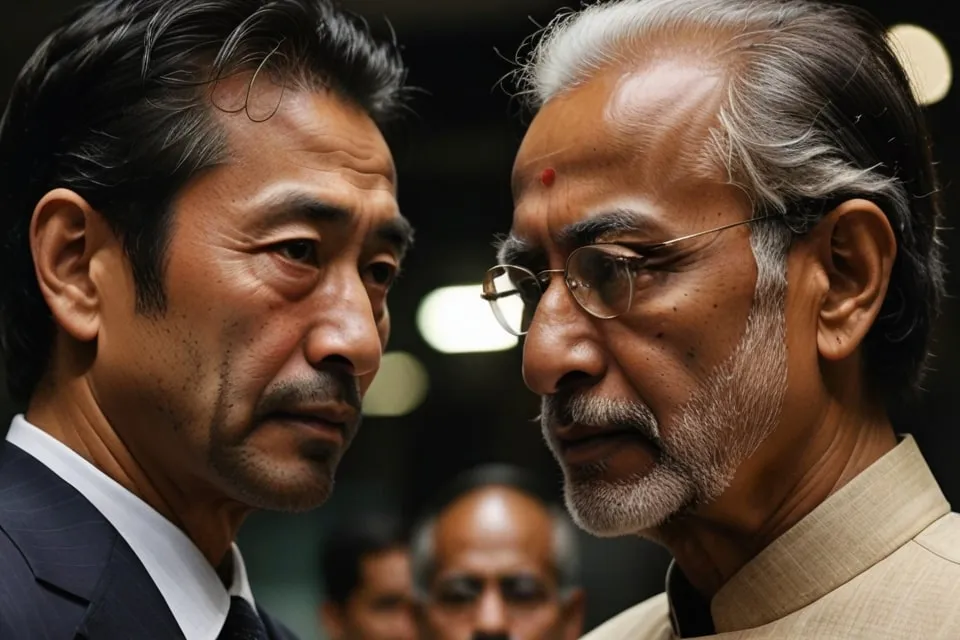

Let's move on to India's economy, which can be summed up in one word: strong.

India's GDP grew by 7.3% in 2023, following a 7.2% growth in 2022, significantly outpacing other major economies. Interest rate hikes have helped curb inflation to below 6%. While this figure might seem high compared to Europe or the US, it's relatively reasonable for a rapidly developing economy like India.

With an inflation target of 4%, a range of 2% to 6% is generally considered acceptable. Unemployment has risen slightly.

Rather than bombarding you with more data, let's address the elephant in the room: India's economic data might be slightly inflated. However, the general consensus is that India has experienced rapid economic growth in recent years, with inflation and unemployment remaining manageable.

So, how are they achieving this high growth in a sluggish global economy?

Many point to geopolitical factors. Recent years have seen a flurry of news about companies seeking to diversify their supply chains away from China, aiming for a "China Plus One" strategy. India, with its low labor costs (roughly half of China's) and a relatively well-educated workforce, is a prime candidate for this shift, particularly in low-end manufacturing.

Apple, for example, has been steadily moving its supply chain to India. A portion of iPhone 15 production has already shifted there. Foxconn has invested approximately \$10 billion in Indian factories. Tech giants like Google and Amazon have pledged a combined \$26 billion in investments in India by 2030.

It's easy to assume that these investments are driving India's economic growth. While partially true, this assumption requires a deeper dive.

The impact of foreign direct investment (FDI) might not be as significant as it seems. While figures vary, even the highest estimates place FDI inflows to India at around \$700 billion, representing only about 2% of India's GDP. Moreover, this figure is at a four-year low, primarily due to a global decline in investment, affecting developing countries the most. The decline in investment doesn't necessarily reflect negatively on India's attractiveness.

The current focus on supply chain diversification warrants further discussion. Several countries are vying for a piece of the pie: India, Vietnam, Mexico, Indonesia, and Thailand. Vietnam, in particular, relies heavily on FDI, which accounts for 4% to 5% of its annual GDP. Mexico has also benefited from increased investment in recent years.

While India's absolute FDI numbers might seem impressive, they pale in comparison to its overall economic size. Furthermore, much of the recent investment is in the early stages of factory construction, with some projects yet to materialize beyond verbal commitments. This means that the impact on GDP growth might not be immediately apparent.

Here's an interesting tidbit about India's FDI: Did you know that the largest investor in India over the past two decades, accounting for a third of its FDI, is Mauritius? Mauritius, an island nation of 1.2 million people in the Indian Ocean, serves as a tax haven. Many companies route their investments through Mauritius to take advantage of favorable tax laws, as seen in the Adani Group scandal. If you're interested, I encourage you to learn more about tax havens.

So, if not FDI or manufacturing, what's driving India's economic growth? The most straightforward answer is government spending on infrastructure.

Take a look at India's government expenditure over the past few years. It has been growing at a rate exceeding 30% annually, reaching over 10 trillion rupees (approximately \$120 billion) in 2023. A significant portion of this increased spending is directed towards infrastructure projects such as road construction, urban development, sanitation facilities, telecommunications infrastructure, and water supply systems. They've even reduced subsidies for the poor and housing allowances to free up funds for infrastructure development.

This strategy should sound familiar to those familiar with China's economic model. Infrastructure spending has a direct and immediate impact on GDP growth.

However, it's not as simple as it sounds. Infrastructure spending is costly, and the money has to come from somewhere. In India's case, it's primarily financed through government borrowing.

For this approach to be sustainable, the long-term returns on these infrastructure investments must exceed the cost of government borrowing, i.e., the interest rates on government debt.

Let's compare this to Japan. Japan's debt-to-GDP ratio exceeds 260%, and yet they continue to borrow at low interest rates (below 1%, and previously even lower than 0.25%). This means that as long as their investments yield a return higher than 0.25%, they can theoretically continue borrowing and investing.

India, despite its rapid economic growth, has much higher interest rates. Their government bond yields hover around 7% and have even reached 9%. Moreover, there are concerns about "leakage" in their infrastructure spending due to corruption, potentially impacting the actual returns on these investments. Whether this level of investment is sustainable remains to be seen. It's worth noting that the largest expenditure for the Indian government in 2023 wasn't infrastructure development, but interest payments on their debt, which consumed a fifth of their budget. And they're continuing to accumulate debt.

This is not to say that India is headed for a debt crisis. However, it highlights that for this infrastructure-driven growth model to succeed, the returns on these investments must be substantial, and the economy needs to grow at a rapid pace to service this debt. Infrastructure spending, despite its allure, is not a silver bullet and requires careful planning and execution.

Beyond government spending, another significant driver of India's economy is consumption, or more broadly, domestic demand. While external demand has been weak, India's economy has historically been relatively insulated from global shocks. Despite efforts to attract FDI and boost exports, their contribution to the overall GDP remains relatively small. This allows India to focus on its own growth trajectory, regardless of external factors.

As a result, India's consumption remains robust compared to other countries, even if it's simply performing at its usual pace.

Of course, we can't discuss India without mentioning its population. India's vast population, coupled with urbanization, digitization, and other factors, has created a massive interconnected market. While not the primary driver of growth in any given year, this demographic dividend provides a long-term advantage. It's like starting each year with a 0.5-point bonus compared to countries with aging populations. This cumulative advantage could be one of India's most significant growth drivers in the long run.

Consider India's female labor force participation rate, which stands at just over 20%. This is significantly lower than other countries. While concerning from a current standpoint, it also highlights a significant growth opportunity. Almost half of India's potential workforce is untapped, representing a vast pool of untapped human capital.

Furthermore, in India, higher education levels are often correlated with higher unemployment rates. This seemingly counterintuitive trend suggests that there might not be enough high-skilled jobs available to meet the growing pool of educated individuals.

While it's possible that highly educated individuals simply have higher job expectations, it also highlights India's potential. They have a large and increasingly skilled workforce ready to be unleashed. In essence, India possesses an abundance of what developed countries crave: a young and growing workforce.

India's future growth faces several potential challenges, including population management, caste-based conflicts, political elections, and wealth inequality. We won't delve into those today.

However, there's one particularly interesting risk factor for India: artificial intelligence (AI).

The year 2023 witnessed the explosive growth of AI. This trend shows no signs of slowing down, and India is likely to be one of the countries most impacted by this technological wave. India is renowned for its IT and services sector, which contributes to over half of its GDP. The rise of generative AI, like ChatGPT, threatens many entry-level jobs in customer service and IT, sectors where India has a significant presence. The Indian government is aware of this challenge and is actively exploring ways to navigate the AI revolution. For India, AI is not just an opportunity but also a challenge to adapt and evolve.

The IMF projects India's GDP to grow by 6.5% in 2024, with inflation easing to 4.6%. The Indian stock market also experienced a bull run in 2023, rising by approximately 20% and reaching record highs. However, it's a market known for its complexities, with insider trading and other issues. Furthermore, the stock market's connection to the real economy in India is relatively weak, so we won't delve into it today.

This article has gotten quite long, so I'll be splitting it into two parts. Otherwise, I'd become a monthly uploader. In the next part, we'll discuss the US economy and its surprising resilience. We'll also explore Germany's economic struggles and delve into my methodology for analyzing complex economic issues.

Stay tuned for the next installment!